7 Visions

- Regain ground

- Author

- Aitor Varea Oro

- Figure

- Ilha na Praça da Alegria, Porto, Aitor Varea Oro, s/data

Each April 25th* celebration puts the spotlight in the SAAL** process, which is a motto for this initiative and which next year will have completed five decades. The exceptionality of that moment and the quality of the architectures produced imprint the act of designing for the most vulnerable an irresistible epic for architects, but one/however incompatible with the current context. The need to solve housing, urgent and serious needs for many requires the answer to be inserted in everyday life. It is not acceptable to wait for the ideal conditions for the exercise of architecture or to limit to simply claim them.

It is about advancing, without delay, in the creation of conditions, for the benefit of who is being left behind.

Architecture students, teachers and educational institutions have the real possibility of changing this scenario, which requires realizing that architecture is produced in partnership with the society in which we live, and that the design begins long before the definition of a building’s construction documents/specifications or bill of quantities. The withdrawal of our class from the space where everything is decided, where exclusion and lack of quality/low quality/absence of quality materialize even before any line is drawn, has to be avoided at all costs. This places a challenge to the practice of architecture. To understand where from can we reconstruct this broken relationship between those who have the problem and those who have the solution, it may be useful to think of this challenge as a climbing with successive stages.

1. Get to know well who you work for. The inhabited and built environment is the stage of the life stories of our generation. We invest a lot of time and energy to debate on the architect's social role, but: do we really know at the service of what and who, are we making our skills available to?

2. Stop being invisible to those who share your concerns. The social workers of the parish councils/local administration, the entities that make up the council social networks or the health professionals of the degraded territories, among others, have in you partners they are unaware of.

3. Master the tools that enable the fair and rigorous construction of spaces. From the areas of urban rehabilitation* to local housing strategies*, there is a whole set of opportunities to provide the resources needed for architectures to come out of paper.

4. Use your skills to spatialize, quantify and program the desires of all the interveners/stakeholders needed to materialize the change. Creating a future image, removing uncertainties, and increasing confidence in the process is the best way to make those involved understand each other and reach agreements.

5. Grow professionally finding unlikely allies who defend together with you, and in your name, with arguments that cannot be imagined and in spaces you don’t have access to, those projects which, by their pertinence, desirability and feasibility, can no longer be imprisoned within the university walls again.

The best recipe for the absence of architecture in the territories of poverty is to inhabit the space prior to the detailing of the design: that of the creation of conditions for its existence. These are not limited to the quantification of housing needs and the allocation of financial resources to solve them. We need a correct spatial formulation of the problems to be solved, otherwise we risk, at the drawing board, to be answering the poorly framed challenges/request from the commission. Practicing our profession/Exercising our practice in areas we withdraw from, is a way to regain ground so that architects can take part, increasingly and in improved ways, in building a fairer society. With each anniversary of SAAL we can reduce the distance that separates us from April 25th. And this increase in democracy in the practice of architecture depends essentially on us.

Translator Note

* (date of the military revolution, known as “carnation revolution”, that ended the dictatorship on April 25th, 1974 and opened the way for democracy (from en.wikipedia.org/Carnation_Revolution)

** (Local Ambulatory Support Service (SAAL), a state housing construction program that emerged after the April 25th,1974 Carnation Revolution, which set out to address the housing needs of underprivileged populations in Portugal. SAAL operations, inserted in the social climate of popular action that characterized the Revolutionary Period of the time, became an international reference in terms of people’s participation in housing and urban design processes. The interaction between technical brigades of architects and the population organized in residents' commissions contributed to what is considered a unique moment in the history of Portuguese architecture. (+ info > pt.wikipedia.org/SAAL)

* By urban rehabilitation area, we designate the territorially delimited area that, due to the insufficiency, degradation or obsolescence of buildings, infrastructure, collective use equipment and urban and green spaces for collective use, namely with regard to Its conditions of use, solidity, security, aesthetics or health, justify an integrated intervention, through an urban rehabilitation operation. www.portaldahabitacao.pt.

The Local Housing Strategy (ELH) is an instrument that defines the strategy of intervention in housing policy. ELH should be based on a diagnosis of existing needs regarding access to housing, resources and transformation dynamics of the areas they refer to, so that the goals and objectives to be achieved in the period of its validity can be determined, and so as to specify the housing solutions to be developed and their hierarchy. It must also articulate the objectives and actions to be developed in the area of housing policy with other sectoral policies, namely urban, social, employment, education, health, mobility, among others. www.portaldahabitacao.pto.

- We need to reactivate the renewable energy of Imagination*

- Author

- Inês Lobo

- Figure

- s/ título, Duarte Belo, 2021

* BERARDI Franco com SALVO Philip

We live today a different time. A time that implies a New City Culture, inseparable from the construction of the future as Collective Work, also and consequently, inseparable of its own Design of the City. Culture and Design that reject functional and social compartmentalization, for they welcome and propose a City of Mixing and Overlapping, complex and ethnic in all its aspects.

It's the time for a new gaze. A gaze that, from Housing to City, combines in the same energy all urban spaces, the Space of Ecological Continuities, the Space of Infrastructures, the Space of Watercourses and Drain Systems, the Public Space, the Space of Soft Modes and the Built Space itself. All as different things of the same thing, where green spaces find wide complicity and resonance. Therefore, a new discipline matters, the Urban Botany, which guarantees diversity and balance. But it matters, too, where not to plant, for the beauty of cities lies equally in its mineralization.

We will then wait for the rainy days with the same intensity with which we wish for those of sunshine, to see the city turn before our eyes into a theatre in which nature is put on stage

It is the time of strategies with different scales and timeframes. On the large scale shalll be found the solutions for cities cross connected at the regional level, cities of enormous diversity, cities that balance their natural and urban systems to ensure resilience, cities that accept the ‘propositum’ of being a living organism in constant transformation.

It is the time to rediscover the profile of our cities, accepting that there are no longer city models, and to produce short term strategies that generate responses in times of emergency.

Cities have established their urban design through processes which have rarely been coordinated by a global idea of growth, but rather due to development opportunities on specific occasions, especially linked to particular events of economic, social and political life, or in response to urgent reconstruction needs in the face of natural disasters. Thus derived the great diversity and complexity of its urban systems, or Parts of the City, by nature inhibitors of the imposition of single rules for the definition of urban design, public space and architecture. However, these same diversity and complexity result in the great richness of their different urban models, associated to communities with intense relations with its Parts of the City.

These Parts of the City are configured in spaces with reasonably homogeneous urban models, but which, through complementarity and reciprocity, also generate relatively indefinite Interstitial or Residual Spaces, often with the prominence of infrastructure even if not always properly articulated with the urban space. However, these Interstitial or Residual Spaces constitute today the large territory of urban transformation, the large reserve of space for the cities of the future.

Here we can find many of the answers to some of the city's main challenges, from housing for the largest number to new public space typologies that adjust the city of the automobile to the human scale. These are the areas that, by their nature and qualities, but also by the urgency of its transformation, may be the answer to the demand for better cities, to the right to the city, to the city for all.

"The greatest purpose of man is not being born to die, it is being born to continue."

Paulo Mendes da Rocha

The idea that we were born to continue takes special pertinence when we think what the transformation of a city should be. And the city, in every moment, is the desire for a perfect place for the life of its community. This condition leaves no doubt about the idea of continuing. It is perpetuating time, it is to continue the preceding time in the present and future time.

We appeal to architects of action, who have long lost the ability of synthesis among the different elements that make up the territory. A new group of architects should rise against a culture in decline that promotes the uncritical production of residue. The use of residue should be the starting point for the regeneration of urban fabric, with the awareness that reuse concerns a choice, and that construction, reuse and demolition are complementary acts of design that must be operated with courage and responsibility: reuse is not always the solution, demolition is not always necessary.

Creation of new value begins with a choice.

- Oecumene: our battlefield

- Author

- Maria Manuel Oliveira

- Figure

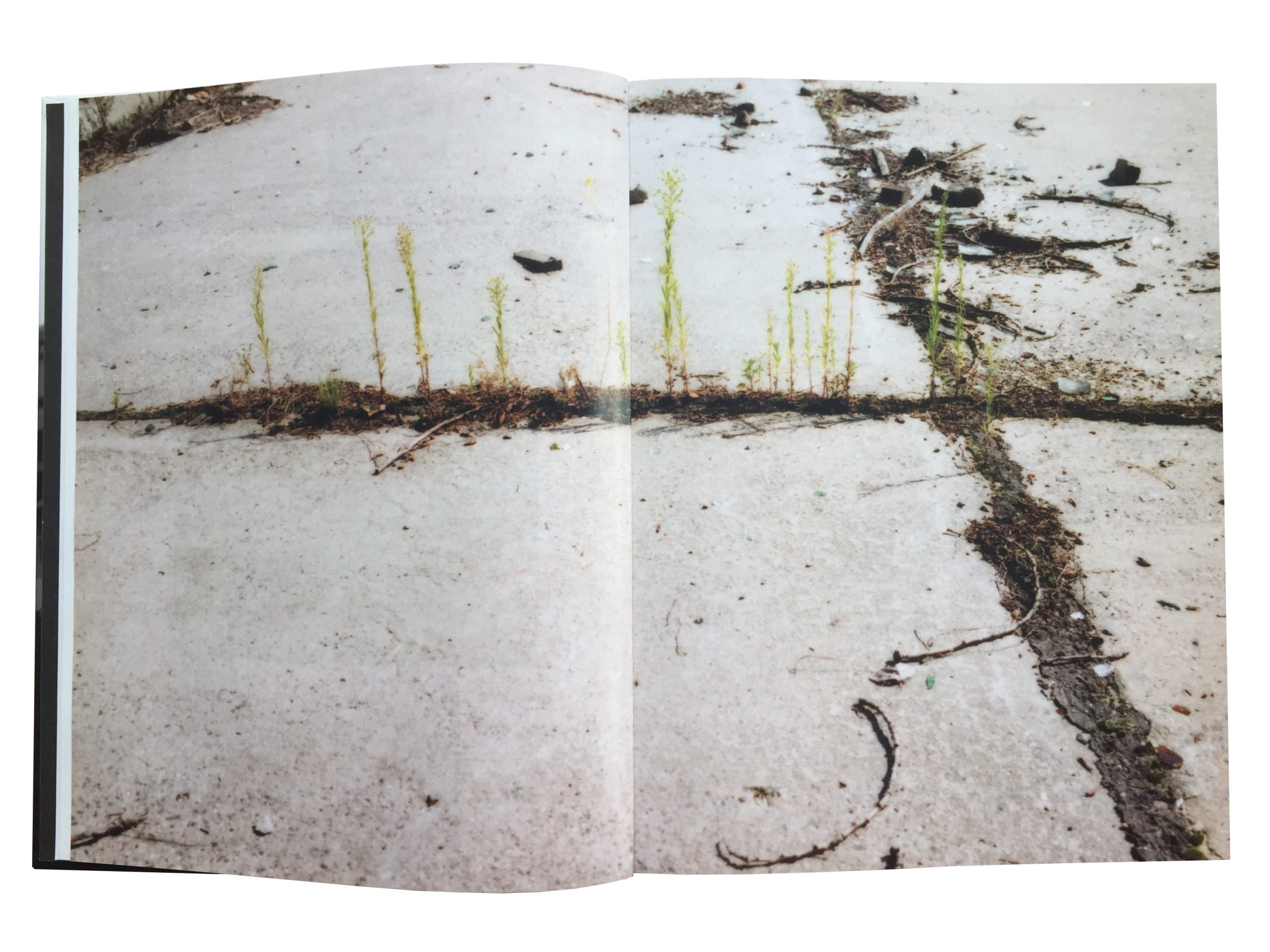

- As raízes também se criam no betão | “Roots also grow in concrete”, Kader Attia, 2018

1.

Saying today that we move in uncertainty is a redundant statement: we know it, surely, since the last decades of the previous century. But we did not imagine the intensity with which it would settle, the speed with which our practices and convictions would confront their potential obsolescence. Between methodological reasons we believe to be perennial and the foam of days, we find ourselves in the eye of the hurricane.

Designing from an unstable threshold permeated by ethical concerns, is our condition. We reflect upon the world and project it in the conviction - we continue to believe - that architecture is [wants to be] a laboratory for building the common good, committed to the already long search for the “happiness of the people”.

In times of digital technoculture, we see basic issues directly related to the subjects of our disciplinary activity amplified - such as the right, for all, to housing, to the city, and to a qualified environment - which tragically and insistently remain in the category of desires/designs unfulfilled.

2.

Responding to the call of the city's lights, the very fast and progressive urbanization we see - expansionist vertigo that continues thriving - has neither led to the provision of housing for all, nor to a city more accessible to all, nor to the definition of environmental policies that effectively improve the conditions of daily life.

In an acceleration that has been showing with perverse effects at multiple levels, this trajectory justified an extractivism without limit and transformed the soil into a mere financial product. In this abstraction the awareness of its relevance in the way we conceptualize and design is diluted. And in the absence of interaction between man and the inhabited ground, it has lost its condition as a founding entity.

Paradoxes are accentuated and reverberate with violence for the most part of humanity that lives in a situation of vulnerability and their social, material and spatial ecosystems. Defending basic principles of disciplinary exercise - will it make sense, perhaps, to recentre the essentiality of the Vitruvian triad? - we need more and better architecture, attentive to renewed and urgent collective commitments.

3.

The severe climate and socioenvironmental crisis we live in, reflected in both the vertical and horizontal metropolis, requires a critical (re)position of our usual practice.

Soil impermeability, not only agricultural and forest, but also urban (now, frequently masked by vegetation simulacres), accompanied by the present abundance of the destruction of the built environment, puts us in the face of an unbearable consumption of resources that is essential to reverse.

No longer conceptualizing the ground in which we move as a mere surface, and find equity relationships between what is extracted and what is returned, between what is destroyed and what is transformed, is a prime basis to our reflection.

The recognition of the soil as a living and porous organism, the importance not only of respecting and preserving it, but of increasing its quantity and amplifying its quality either in new construction or in built fabric, contains the foundations for an architectural and urban action alternative.

4.

1.

Saying today that we move in uncertainty is a redundant statement: we know it, surely, since the last decades of the previous century. But we did not imagine the intensity with which it would settle, the speed with which our practices and convictions would confront their potential obsolescence. Between methodological reasons we believe to be perennial and the foam of days, we find ourselves in the eye of the hurricane.

Designing from an unstable threshold permeated by ethical concerns, is our condition. We reflect upon the world and project it in the conviction - we continue to believe - that architecture is [wants to be] a laboratory for building the common good, committed to the already long search for the “happiness of the people”.

In times of digital technoculture, we see basic issues directly related to the subjects of our disciplinary activity amplified - such as the right, for all, to housing, to the city, and to a qualified environment - which tragically and insistently remain in the category of desires/designs unfulfilled.

2.

Responding to the call of the city's lights, the very fast and progressive urbanization we see - expansionist vertigo that continues thriving - has neither led to the provision of housing for all, nor to a city more accessible to all, nor to the definition of environmental policies that effectively improve the conditions of daily life.

In an acceleration that has been showing with perverse effects at multiple levels, this trajectory justified an extractivism without limit and transformed the soil into a mere financial product. In this abstraction the awareness of its relevance in the way we conceptualize and design is diluted. And in the absence of interaction between man and the inhabited ground, it has lost its condition as a founding entity.

Paradoxes are accentuated and reverberate with violence for the most part of humanity that lives in a situation of vulnerability and their social, material and spatial ecosystems.

Defending basic principles of disciplinary exercise - will it make sense, perhaps, to recentre the essentiality of the Vitruvian triad? - we need more and better architecture, attentive to renewed and urgent collective commitments.

3.

The severe climate and socioenvironmental crisis we live in, reflected in both the vertical and horizontal metropolis, requires a critical (re)position of our usual practice.

Soil impermeability, not only agricultural and forest, but also urban (now, frequently masked by vegetation simulacres), accompanied by the present abundance of the destruction of the built environment, puts us in the face of an unbearable consumption of resources that is essential to reverse.

No longer conceptualizing the ground in which we move as a mere surface, and find equity relationships between what is extracted and what is returned, between what is destroyed and what is transformed, is a prime basis to our reflection.

The recognition of the soil as a living and porous organism, the importance not only of respecting and preserving it, but of increasing its quantity and amplifying its quality either in new construction or in built fabric, contains the foundations for an architectural and urban action alternative.

4.

To care, maintain, build strictly and solely the indispensable, not to demolish, repair, reuse, include the thickness of the soil in the cycle of exchange that any intervention always presupposes... The concept of heritage thus becomes the object of another look: It is associated with a new perspective, one which seeks the qualities of the ordinary and the usual, defending a comprehensive strategy of maintenance and reuse that seeks to dramatically reduce waste and predation.

What conceptual realignments, in the way we design and build, does this approach put to us architects? These are, so far, more questions than answers and we need to build them simultaneously, deeply crossed as they are. Architecture is “a laboratory of the future”. More than ever, architects are needed in interaction with other areas of knowledge, stimulating creative and responsible action that incorporates recent understanding and uncertainty as data of the problem, in the assumption that aesthetics and ethics are inseparable.

Without nostalgia and without fetishisms, old or new, we need to believe in disciplinary intelligence, facing the lack of knowledge with positive energy, in this search metabolizing the complexities and hierarchies that contemporarily inform the design decision. And open to differences and juxtapositions, in the illuminated zones and in the shadows we will study and design, discovering through critical thinking and through the exercise of drawing, new echoes and resonances.

Que realinhamentos concetuais, na maneira como projetamos e construímos, esta abordagem nos coloca a nós, arquitetos? São, ainda, mais as perguntas que as respostas e precisamos de as construir em simultâneo, profundamente cruzadas que estão. A arquitetura é um laboratório do futuro.

Mais do que nunca são necessários arquitetos, que em interação com outras áreas do saber estimulem uma ação criativa e responsável, que incorpore saberes e dúvidas recentes como dados do problema, no pressuposto que estética e ética são indissociáveis.

Sem nostalgia e sem fetichismos, antigos ou recentes, precisamos de acreditar na inteligência disciplinar, enfrentar os desconhecimentos com energia positiva, nessa busca metabolizando as complexidades e hierarquias que contemporaneamente informam a decisão projetual.

E disponíveis às diferenças e às justaposições, nas zonas iluminadas e nas sombras estudaremos e criaremos, fazendo reverberar, pelo pensamento crítico e pelo exercício do desenho, novos ecos e ressonâncias.

- More than Houses, Simply Houses, Simple Houses

- Author

- Nuno Brandão Costa

- Figure

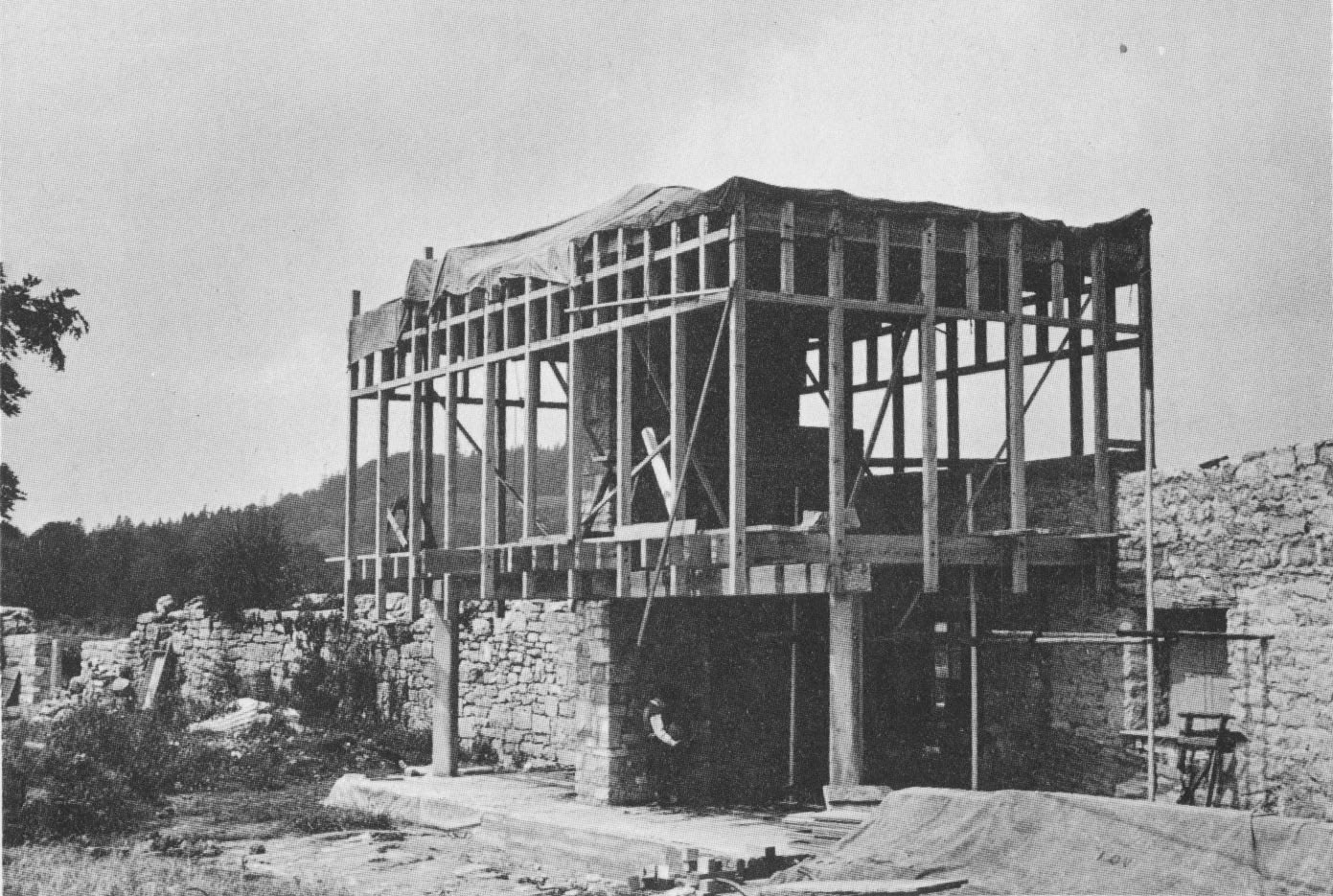

- Alison e Peter Smithson, “Upper Lawn Solar Pavilion Folly”, 1959-62, Wiltshire, cortesia Smithson Family Archive

The architect is the only professional, technically and socially qualified, to design houses, whether these are private single family homes or private and/or public collective housing buildings. As a result, it is the one that defines urban morphology, given the impact of housing, on the generic definition of urban fabric (Rossi) and public space.

The period in our country (Portugal) is particularly tense, given the extreme lack of accessible housing, namely in urban centres and for socially disadvantaged groups, but also for the average population. The (Post-Pandemic) Western European political-economic context allowed access to considerable funding for the constitution of a large-scale offer of multiple public architectural design competitions for the development of public housing programs, accessible to all architects, without exception and without obstacle.

Paradoxically, the architects are faced with a crossroads. On the one hand, the promoter/developer, at the time of evaluating the design proposal, proves conservative and conventional (in the worst direction, towards the prior stipulated), giving no room for experimentation of the typological proposal, for the critical possibility of the housing program or the construction reseach (although the commission requests emphatically suggest attention to sustainability issues, in practice these become irrelevant in the selected solutions, which exposes the superficiality with which the theme is rhetorically elaborated). In addition, the entropy of endless and extremely rigorous regulations that contradict each other and introduce a superlative expense in the construction, already crushed by the maximum cost corset by m2 (which, for example, nullifies the possibility of using Eco Materials, which in the market economy present an exorbitant price compared with current materials, contrary to the objectives stated). Also, add the idea of a widespread prejudice in the target population, before uncommon inhabiting and spatial solutions, which motivates an immediate apprehension from the developer. Even when this variation is subtle, or merely hinted.

On the other hand, the academic context and the so-called scientific or critical journals, crystallizes, bored and bogged down in the emptiness of questioning, in the permanent historical revision-reinscription (still very much captured, by the defunct postmodernity), betrayed by the relativism of the ideological lines, the immediacy and superficiality of consecutive adherence to contemporaneity and consequently the constant attempt to thematic update according to emerging subjects (which emerge permanently, becoming immediately obsolete) and the obsession with transdisciplinarity, which reaches paranoia levels (see some doctoral theses and scientific articles’ titles). An environment much populated by architects who despise architects and architecture (an originality of our class). As in the previously described context, of real comissions, ARCHITECTURE and above all its core - the practice of DESIGN - also fades in this context. This world is no longer for Ludwig Hilberseimer and Mies Van Der Rohe, neither for Le Corbusier, nor for the Smithsons, much less for Filippo Brunelleschi or Andrea Palladio.

The precedents are not the most convenient. Postmodernism ignored the typological exercise (an act that was too modern, rational and spatial, therefore cold and aseptic...) and offered an epidermal, pop-aesthetic panoply for real estate speculation to sell the colorful and/or deconstructed city or even the countryside, if necessary. In the meantime, the colors faded and the mirrored windows fogged up, revealing a sinister city, aged without dignity and without true houses. Perhaps, the solution will also not be that of its legacies, from digital formalism to picturesque tectonic historicism or the Hyper reactions of minimalist formalism, which, in order to appear simple, is full of sophisticated details, and successive layers. All respectable and proportionate, but perhaps formally and ecologically, not very sustainable.

In recovery interventions (a very dubious term) the graceful appearance of a reconstruction of the image of history (a non-existent history) prevails, even if everything is demolished to be rebuilt, or a garage door is placed where there used to be a window of a grocery store. The stone portal will have to “remain”, now only 2 cm thick, framing the UPVC sectional door, and the roof obviously in ceramic tile. A theoretical succession of aberrations, implacably imposed on architects by experts in heritage (?).

The architectural design, and its experimental component, seems to be an almost undercover possibility. Nothing new: half a century ago, in Porto, the architects of the SAAL process, alien to mainstream vanguards and pedagogical semiotics, made a typological invention to bring about the revolution. Siza designed a house with a staircase going up in reverse and Pedro Ramalho designed a duplex with just one wall, both looking at the social-democratic “Siedlungen” of the Weimar Republic. It was always from the center of Europe that the most thrilling typological references emerged, the more liberal environment and the frugal and rigorous culture, Protestant and Calvinist, seem more elastic. Between Friedrishain's old Berliner-Zimmer and Michael Alder's experimental typologies in Basel (Das Haus als Typ), there is a whole fascinating and endless world of hypotheses for organizing living space.

As for sustainability, an inevitability, which for great architects has always been self-evident, before being pompously enunciated:

More than three decades ago, Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron built a house in Tavole, with a wonderful plan, designing the living space from a single cruciform structural wall, erected in situ, filled with local stone, collected in place.

Shortly afterwards, they set up an industrial building to store sweets made from aromatic plants, built with a structure made entirely of wood, finished with prefabricated panels made from recycled materials, producing the stunning effect and monumentality of a Renaissance palace.

At the same time, Eduardo Souto de Moura built a market, with only two rows of pillars and a slab, a stone wall from the region, with the whole space naturally lit and ventilated.

Let us go back another three decades, to the time of the construction of the Upper Lawn Pavilion by Alison and Peter Smithson. A solar dream, a masterpiece of domestic experimentation, made from the existing walls of a building that remained (the Solar Pavilion Pavilion is in fact a reconstruction), added of a modulation of carpentry and glass, two wooden columns and empty space:

Simply a house. A simple house.

- Gleaning Past Residential Architecture as an Act of Resistance

- Author

- Rui Jorge Garcia Ramos

- Gisela Lameira

- Tiago Lopes Dias

- Figure

- “Déchets”, Julie Nahon, 2019, a partir da pintura “Des Glaneuses”, Jean-François Millet, 1857

The urgency of housing for a significant part of the population, capable of tackling adversity and uncertainty, of being inclusive and intergenerational, of translating cultural and participatory processes, as part of the response to the contemporary societal crisis, goes beyond the proposal of new housing models and requires the acknowledgement that these challenges have existed throughout history. Thus, the response to today's indisputably pressing problems gains depth when elaborated in the longue durée of the experience of housing construction in the 20th century and in the understanding of its foundations and logic.

In the early 20th century, the housing problem determined the implementation of mass construction programs from Berlin to Frankfurt, Vienna and Amsterdam, promoting access to decent housing and also to the city itself. This process also leveraged the redefinition of housing and ways of living to attain a response to the challenges of its time, implementing ideological visions such as minimum housing and the Frankfurt cuisine as spaces suited to modern life.

Simultaneously, research into the plan libre and the direct and indirect resources of flexibility, polyvalence, adaptation, and reversibility boosted the continuous experimentation of adaptable types. The possibility of organising space independently of structural constraints, conveyed in new materials and construction techniques, paved the way for housing composition and distribution strategies that would be explored by different architects throughout the following generations in the proposal of inclusive, resilient domestic spaces, adapted to the intrinsic variability of living.

In the post-war period, the main focus of research was geared towards local constructive and material resources, and above all, human resources, i.e., communities and the way they inhabit, how they use and appropriate space. The thirty glorious years made it possible for Western democratic states to put into practice fundamental experiments such as the involvement of citizens in the housing process through public consultations, prior investigation into their needs, and even direct participation through self-management (cooperative model) or self-construction, and these experiences underpinned the right to housing and the right to the city.

In the challenging context of the “Estado Novo” dictatorship in Portugal, some of these issues began to be addressed by architects working at the service of institutions such as the Federation of Provident Funds (“Federação das Caixas de Previdência”) and the National Laboratory of Civil Engineering, which allowed them, with some degree of autonomy, to establish solid work bases and well-prepared technical teams. However, it would only be possible to move swiftly towards alternative ways of thinking and building housing after the revolution of 25 April 1974, with the SAAL program (Local Ambulatory Support Service).

The fact that SAAL constituted an opposition to the liberal models that dictated conventional accommodation systems limited its action. Likewise, the international context of the 1980s, after the oil crisis of 1973, leveraged the dilapidation of the housing policy implemented since the founding of the FFH (Housing Development Fund/ “Fundo Fomento Habitação”, 1969), with the conviction that social/affordable housing was a task for which the State was not responsible, replacing it, solely and illusively, with the intentions of the real estate and financial market.

The contemporary discussion of the housing problem has been driven in Portugal by political strategies, translated into legislative changes such as the enactment of the New Generation of Public Housing Policies (2018), the Basic Housing Law (2019), and the recent approval by the government of the “Mais Habitação” (2023) package of measures.

Although political, this discussion is also eminently architectural and should incorporate the update of housing types and models (in a logic opposite to the idea of a standard project), going beyond crystallized proposals. This trivialization of collective housing is, in part, the result of a selective appropriation of utopia and the Modern Movement's project proposals for society, distorting them in the face of everyone's complacency and the interest of some. Among other aspects, this process has given rise to solutions that are not very resistant to changes in lifestyles reflected, for example, in situations of intergenerational coexistence, activities such as working from home, or general issues such as adapting to the ageing of the inhabitants or adequacy to energy efficiency criteria.

However, the results of the recent holding of numerous tenders for the creation of affordable rental housing, both at the municipal level and promoted by the Institute for Housing and Urban Rehabilitation (IHRU, I.P.), are worrying as they point in the opposite direction. At the level of the elaboration of tender programs, conventional distribution systems are induced and limit the aforementioned typological research. Also, in the juries' evaluation of the proposals, and within the scope of competition rules, they are not aware of other proposals that may reflect the successful/failed experiences of a century of collective housing. Among others, these aspects disregard the diversity of ways of living and the transformation of living space throughout life as a necessary expression of architecture's durability and a sine qua non condition for sustainability. sine qua non de sustentabilidade.

Thus, in Portugal, the disciplinary discussion of Architecture, and particularly design practices and the analysis mechanisms of architectural design, need to incorporate today's fundamental issues such as the multiplicity of ways of living and their natural variation, together with aspects such as demographic movements, population ageing, and climate change. These factors represent a necessary and specific contribution from architects in the face of current challenges, in an inclusive, resilient, and diversified response to timeless problems such as accessibility, spatial requirements, adaptation to circumstances and ways of life over time, or the need to respond to sustainable building standards. These practices and solutions present in housing from the past are of interest today to be carefully gleaned.

(Note: This abstract was prepared based on an article where the authors expand on the presented topics in more depth.)

- Teaching as Activism (notes for territorial integration)

- Author

- Sílvia Benedito

- Figure

- Distrito Arganil, Março 2019 (pós-incêndio), Sílvia Benedito, 2019

The President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, on the occasion of presenting the European Green Deal—a strategy to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050—made an appeal: that economic growth and production/consumption methods should be reconciled with our planet and its people. In this mission, von der Leyen emphasized the need to "leave no one behind" 1. What does leaving no one behind mean in the context of teaching architecture/landscape architecture? How can we ensure an inclusive and comprehensive integration of vulnerable territories and communities in the pedagogical sequence?

The last century has witnessed an exponential concentration of wealth and people in cities. For instance, the UN declared that in 2007, the global urban population had surpassed the global rural population for the first time. This accumulation of people implies the accumulation of capital and events, cultural diversity and innovation, housing and retail, infrastructure, and investments, among others. Such concentration of built “things,” people and wealth also represents increased access to employment and job opportunities for our professions—architects and landscape architects. While the education of these professions has been dominated by urban issues, the rural space and its communities have been left behind… What does it mean to teach architecture and landscape architecture focused on rural territories? Does it entail applying the same scopes of work as in more densely populated areas? Despite being challenging, these questions also present the opportunity to reflect on how our professions and teaching methodologies can contribute to these low-density territories.

Let us recall two circumstances: one optimistic and the other not so much. When President von der Leyen launched her integrating directive in 2019, the world was experiencing the first major pandemic of the 21st century, leading cities worldwide to enter lockdowns, and the global distribution of products faced a crisis. In this context, the rural territory, previously left behind, became a potential escape: a place far from crowded urban areas, offering more affordable housing prices, and green spaces that allowed people to breathe freely (without masks). For example, in England, The Guardian wrote "Escape to the country: how Covid is driving an exodus from Britain’s cities," reporting on numerous families who, enabled by the possibility of working online, exchanged their urban residences for new locations in the countryside. Rural areas became the locus of an urban exodus, leading to an activation of the rural real estate market and potential speculative growth. Guardian escrevia “Escape to the country: how Covid is driving an exodus from Britain’s cities”, reportando as inúmeras famílias que, usando a possibilidade de trabalhar online, trocaram as suas residências urbanas por novos locais no “campo”2. If the rural context appears in this scenario associated with a more decentralized and inland-oriented future, the increasing social and ecological degradation manifested in the growing wildfires in Portugal (and other Mediterranean climate areas) reveals endemic problems stemming from long decades, which also result from an opposite migration pattern—outward from rural territories.

“Leaving no one behind,” as a premise in the teaching of architecture and landscape architecture, can amplify both the "good" and "bad" aspects that these two contrasting realities bring to rural territories. As a way to amplify the “good,” one can imagine the design teaching practices embrace some strategies:

1.

Reconnect gastronomic products with the landscapes that produce them as a way to catalyze local production and the landscape mosaic;

2.

Implement regenerative practices for the protection of natural resources, especially water and biodiversity;

3.

Decentralize healthcare services, corresponding infrastructure, and housing to support, for instance, retired populations in their desire to return to rural areas for an improved quality of life and social life;

4.

Identify availability of “housing-stock” that fairly and inclusively accommodates immigrant communities and triggers the renewal of abandoned residential areas;

5.

Empower professions and nature-based activities that contribute to landscape maintenance and soil protection, such as pastoralism and the role of herbivores in ecosystem robustness;

6.

Amplify the aesthetic potentials of the rural world—not in a romantic or naïve way but in a manner that allows society to recognize its unique relevance in promoting resilience in the current climate crisis.

1https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_19_6749

2“Escape to the Country: How Covid Is Driving an Exodus from Britain's Cities.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 26 Sept. 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/sep/26/escape-country-covid-exodus-britain-cities-pandemic-urban-green-space.

- More than Housing – The Voice of the Schools

- Author

- Sílvia Leiria Viegas

- Figure

- Bairro da Torre, Camarate (Loures), Sílvia Viegas, 2017

More than 50 years ago, Lefebvre (1968) formulated the idea of the right to the city as a superior right, arguing that space is a product of the social and that the political production of urban space follows and reproduces class systems. Infrastructural housing is a relevant dimension of this produced space, with a market value, for which the author claims a close articulation with other fundamental dimensions: education, work, health, leisure, in short, life in general; there are also multiple singular moments of participation and social realisation, corresponding to different materialities.

In Portugal, the great housing crisis that has marked almost the same 50 years of urban life in democracy draws attention to this conceptual unfolding, translated on the one hand into a structural and systemic context of capitalist governance, and on the other into the experience of people in their everyday lives.

From a socio-spatial point of view, in the metropolises of Lisbon and Porto, problems of gentrification, touristification and the attraction of foreign capital are increasing, leading to processes of overcrowding or exclusion and evictions. At national level, issues of development and territorial cohesion are identified, with imbalances and lack of resources and opportunities in medium and small urban areas and/or rural areas. In terms of migration, there are around 700,000 foreigners in Portugal, 7% of the national total, as a result of the recent growth trend that slowed down during the pandemic. Most of them are concentrated in Lisbon (42 %), Faro (15 %), Setúbal (10 %) and Porto (8 %), while the interior has a residual number 1.

Never before have there been so many public funds and measures aimed at solving the aforementioned housing problem. The New Generation of Housing Policies (2018) 2and its specific programmes, accompanied by the Basic Housing Law (2019) 3, among other instruments of local execution, were followed by the European response to the pandemic (PRR 4 , 2021/2026). The Mais Habitação package (2023) 5, with strong state intervention, aims to regulate the property market in a context of Russian-Ukrainian war and strong economic and social instability. At the same time, expressions and mobilisations of resistance against the growing difficulties are expanding, from the pioneering Caravan for the Right to Housing (2017) 6 with national itinerary, to the Fair Life movement (2023) 7 in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area.

The immigrants who give a face and a voice to the disadvantaged people living in vulnerable situations in Portugal are many and varied: from Africans (and Afro-descendants) from Portuguese-speaking countries who have been living for many years in the peripheral areas of the capital, to refugees of various nationalities, some of them dispersed throughout the national territory, to invisible rural workers in a situation of housing negligence, among many other examples. These people, some of them racialised, from different backgrounds, cultures and religions, with different traditions, customs, habits and/or lifestyles, with individual and collective needs, desires and expectations, are part of the changing urban society that such a system of governance advocates as being open and intercultural.

We are therefore at a unique moment when the forces seem to be at work to build alternatives that respond to diversity: policies claim to be aligned, people and/or communities want to participate, and there is great financial support to intervene. How to seize this opportunity? How does the activist monologue become a dialogue with decision-makers? How does this dialogue inform policy to change practices? How to express the plurality of uses in the new spatial configurations? What morpho-typological and constructive responses need to be explored? These are some of the questions that the school needs to think about and answer.

Lefebvre, H. ([1968] 2009). Le droit à la ville. Anthropos.

Ideas

Calendar

7 DEZEMBRO 2023 | Encontro Chamada de Ideias - Abril 2074 #1

6 MARÇO 2024 | Encontro Chamada de Ideias - Abril 2074 #2

2/3 MAIO 2024 | Encontro Chamada de Ideias - Abril 2074 #3

Exchanges

Publications

Call for Papers

Starbursting

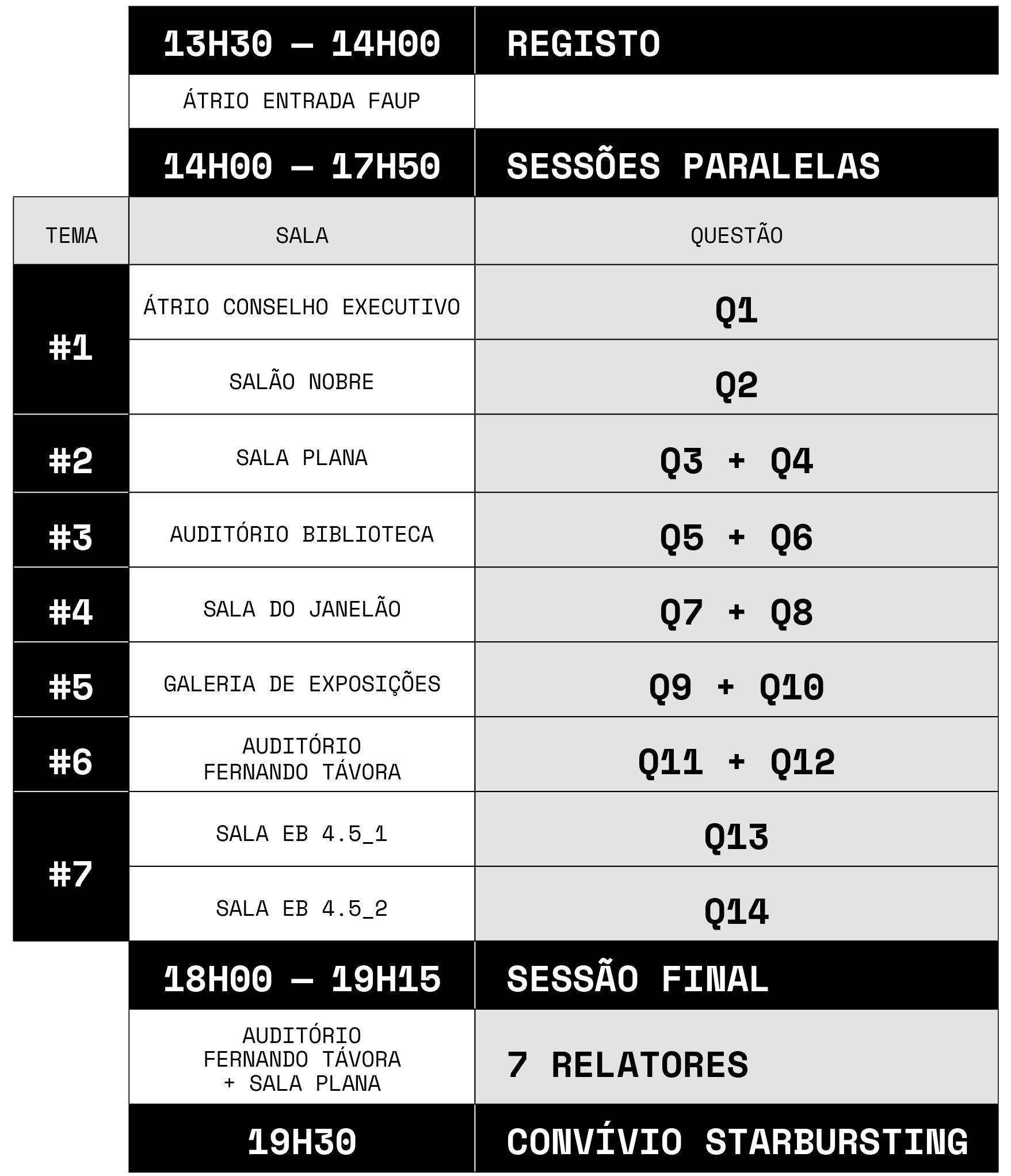

STARBURSTING é uma forma de brainstorming que procura gerar camadas de questionamento em vez de respostas unívocas e imediatas.

Como vamos habitar em 25 de Abril de 2074?

The Mais do que Casas STARBURSTING ambiciona desconstruir esta pergunta complexa através de um desdobramento temático que espelha a diversidade de problemas com que a Arquitetura, entendida num espectro disciplinar lato, se confronta contemporaneamente.

Nesse sentido, definem-se SETE temas e um conjunto inicial de perguntas, DUAS perguntas por tema, que decorrem do Manifesto “Mais do que casas”.

No evento, a decorrer no dia 12 de fevereiro de 2025 nas instalações da Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade do Porto (FAUP), propõe-se uma discussão estruturada em CATORZE sessões paralelas. As propostas apresentadas resultam de uma chamada de artigos, com revisão cega por pares.

Cada sessão instiga a discussão sobre UMA pergunta concreta, espoletando novas perguntas: “como”, “quem”, “quando”, “o quê”, “onde”, “porquê”, serão as dúvidas ou inquietações que procuram adensar a discussão, refinar pontos de vista e perspetivas de abordagem, mais do cristalizar soluções específicas.

→ Participação gratuita, inscrição prévia

QUESTIONAMENTO

#1 – CIDADE E ESPAÇO PÚBLICO

Q1. Como criar modelos de cidade inclusiva através da habitação?

Q2. Que soluções habitacionais para a gestão dos vazios urbanos?

#2 – MODELOS DE HABITAÇÃO

Q3. Como desbloquear inovação nas tipologias de habitação?

Q4. Como renovar modelos de habitação em contextos regulamentares restritivos?

#3 – POLÍTICAS DE HABITAÇÃO

Q5. Que alternativas às atuais políticas de resposta à crise da habitação em Portugal?

Q6. O que se retira do programa SAAL na reposição do direito à cidade e à habitação?

#4 – REABILITAÇÃO

Q7. Como equilibrar as metas Net-Zero com a preservação do património habitacional?

Q8. Que abordagens inovadoras da reabilitação urbana promovem a habitação sustentável?

#5 – ENCOMENDA PÚBLICA

Q9. Qual o balanço crítico aos concursos de conceção promovidos recentemente pelo IRHU e pela SRU?

Q10. Em que medida os programas dos concursos públicos condicionam a proposta de modelos de habitação renovados?

#6 – HABITANTE

Q11. Como incluir os habitantes nas decisões que desenham o ambiente construído residencial?

Q12. Como facilitar o acesso dos habitantes às atuais medidas de apoio à habitação?

#7 – ADAPTAÇÃO ÀS ALTERAÇÕES CLIMÁTICAS

Q13. Como criar soluções responsivas e socialmente participadas de adaptação do espaço público às alterações climáticas?

Q14. Como otimizar o uso de sistemas passivos e condições locais em modelos de habitação sustentável?

Linhas Temáticas

#1 – CIDADE E ESPAÇO PÚBLICO

Q1. Como criar modelos de cidade inclusiva através da habitação?

Q2. Que soluções habitacionais para a gestão dos vazios urbanos?

Habitação acessível, mobilidade eficiente, espaços sociais e equipamentos em rede, acessibilidade a pessoas com necessidades diversas, entre outros, são fatores chave na construção de sociedades sustentáveis e inclusivas, tendo a Arquitetura um papel fundamental não só na remoção de barreiras arquitetónicas, mas fundamentalmente no planeamento de um ambiente construído integrado. A habitação é uma peça chave na estruturação de espaços urbanos inclusivos. De igual modo, na gestão da cidade e do espaço público, os vazios urbanos representam um desafio crítico e oportunidades para o desenvolvimento de soluções inovadoras de reutilização. Este desafio levanta a discussão sobre estratégias para conjugar o potencial destes espaços com as necessidades e aspirações das comunidades locais.

#2 – MODELOS DE HABITAÇÃO

Q3. Como desbloquear inovação nas tipologias de habitação?

Q4. Como renovar modelos de habitação em contextos regulamentares restritivos?

Considera-se que a abordagem ao projeto da habitação deve ser holística, interligando desafios societais como o envelhecimento da população, as alterações climáticas, a eficiência energética, os processos participativos, a adaptação a padrões de vida em mudança, o conforto e o bem estar, entre outros, colocando a Arquitetura e a investigação através do projeto numa posição central de debate. Nesse sentido, a discussão contemporânea do “problema da habitação”, além de política, é também eminentemente arquitetónica e, por conseguinte, deverá incorporar a vertente da atualização de tipos e modelos de habitação (numa lógica oposta à ideia de projeto-tipo), ultrapassando propostas cristalizadas. Os modelos (ainda) vigentes conformam, entre outros aspetos, soluções pouco resistentes a alterações dos modos de vida que possam refletir, por exemplo, situações de convívio intergeracional, atividades como o trabalho a partir de casa, ou questões gerais como a adaptação ao envelhecimento dos habitantes ou a adequação a critérios de eficiência energética. Contemporaneamente, urge instigar e desbloquear processos que promovam inovação e renovação das tipologias de habitação.

#3 – POLÍTICAS DE HABITAÇÃO

Q5. Que alternativas às atuais políticas de resposta à crise da habitação em Portugal?

Q6. O que se retira do programa SAAL na reposição do direito à cidade e à habitação?

A discussão contemporânea da crise habitacional tem sido impulsionada em Portugal através de estratégias de carácter político, traduzidas em alterações legislativas como a promulgação da Nova Geração de Políticas Públicas de Habitação (2018), da Lei de Bases da Habitação (2019), e da recente aprovação pelo governo do pacote de medidas Mais Habitação (2023). O debate em torno das políticas de habitação espoleta também uma reflexão sobre o legado do programa SAAL na luta pelo direito à cidade e à habitação, demonstrando o potencial dos processos inclusivos e participativos. A revisita ao programa SAAL surge então como mote para o desenho de estratégias futuras, questionando sobre a possível integração e adaptação dos seus princípios a estratégias contemporâneas. Ao refletir sobre as atuais políticas de habitação e sobre o SAAL lança-se assim o debate sobre alternativas inovadoras de resposta à crise da habitação em Portugal.

#4 – REABILITAÇÃO

Q7. Como equilibrar as metas Net-Zero com a preservação do património habitacional?

Q8. Que abordagens inovadoras da reabilitação urbana promovem a habitação sustentável?

A reabilitação é um meio reconhecido e eficaz para a redução do consumo global de energia. Este entendimento desencadeou a promoção de medidas como a “renovation wave” com o objetivo de melhorar a eficiência energética dos edifícios e os padrões de vida dos Europeus, reduzindo as emissões de carbono e combatendo os elevados índices de pobreza energética. Estas ações de reabilitação devem, no entanto, acautelar a preservação do património habitacional. O desafio de equilibrar as metas Net-zero levanta o debate sobre a definição de medidas de reabilitação energética que respeitem a integridade e a identidade histórica dos edifícios. Neste âmbito, abordagens inovadoras são essenciais para alcançar habitações energeticamente sustentáveis, o que inclui o uso de energias renováveis, materiais eco-friendly e a criação de comunidades autossuficientes. O debate sobre as práticas de intervenção correntes, na dupla vertente de preservação do património e de promoção de sustentabilidade na habitação, é essencial para a inovação no sector da construção.

#5 – ENCOMENDA PÚBLICA

Q9. Qual o balanço crítico aos concursos de conceção promovidos recentemente pelo IRHU e pela SRU?

Q10. Em que medida os programas dos concursos públicos condicionam a proposta de modelos de habitação renovados?

Segundo o Instituto da Habitação e da Reabilitação Urbana (IHRU), esta entidade lançou, desde 2020, 26 concursos de conceção, a que correspondem um total de 2.816 habitações, “Dando continuidade à estratégia estabelecida para dar resposta às famílias que não têm capacidade de aceder a uma habitação no mercado livre”. Estes concursos promovem a construção de habitações enquadradas no regime de Habitação a Custos Controlados (HCC) e destinam-se a arrendamento no âmbito do Programa de Arrendamento Acessível (PAA). Paralelamente, a Sociedade de Reabilitação Urbana (SRU) tem levado a cabo em Lisboa a construção de habitação a custos acessíveis promovida pelo Município, através de programas de habitação pública enquadrados na Nova Geração de Políticas Públicas de Habitação. Estas iniciativas avolumam concursos, projetos e obras já construídas, constituindo matéria relevante de reflexão sobre a resposta pública aos problemas da Habitação em Portugal.

#6 – HABITANTE

Q11. Como incluir os habitantes nas decisões que desenham o ambiente construído residencial?

Q12. Como facilitar o acesso dos habitantes às atuais medidas de apoio à habitação?

Face ao contexto atual em que a qualidade dos espaços e o acesso à habitação se destacam como questões preementes, torna-se imperativo assegurar a participação ativa dos habitantes na tomada de decisões. Os processos participativos e de cocriação surgem como estratégias fundamentais para o desenvolvimento de espaços mais inclusivos, e comunidades sustentáveis e resilientes. O envolvimento dos habitantes desde a fase inicial dos processos assegura, também, uma resposta mais assertiva e ajustada às suas necessidades e expectativas. Medidas como a criação de canais de comunicação acessíveis e a implementação de novos programas e políticas de gestão são igualmente essenciais para garantir um acesso democrático aos recursos e instrumentos de financiamento disponíveis. Promover o envolvimento ativo e eficaz dos habitantes nos processos e agilizar o acesso a medidas de apoio preconizadas pelos instrumentos em vigor são práticas urgentes, que importa contextualizar em Portugal.

#7 – ADAPTAÇÃO ÀS ALTERAÇÕES CLIMÁTICAS

Q13. Como criar soluções responsivas e socialmente participadas de adaptação do espaço público às alterações climáticas?

Q14. Como otimizar o uso de sistemas passivos e condições locais em modelos de habitação sustentável?

Num contexto em que as cidades são afetadas por múltiplas pressões (ambientais, sociais e económicas), aumenta a vulnerabilidade social à poluição atmosférica, ao ruído e às temperaturas extremas, fatores que interagem e têm maior impacto na saúde e na qualidade de vida da população com menos recursos económicos, pessoas mais velhas e crianças. A adaptação às alterações climáticas exige, de igual modo, o desenvolvimento de modelos de habitação sustentável. O uso de sistemas passivos como a orientação solar, a ventilação natural ou dispositivos de sombreamento, aliados à otimização das condições naturais do local como o clima (temperatura e ventos dominantes) e a geografia (topografia e vegetação) contribuem para a redução da dependência de meios mecânicos e para a mitigação dos impactos ambientais associados à construção. Criar soluções participadas e otimizadas, tanto no desenho do espaço público como na conceção dos edifícios de habitação são desafios prementes em Portugal, tendo como referência outros países em se verifica um lastro de experimentação com maior consolidação.

Call for Papers

A chamada de propostas está aberta a toda a comunidade académica e científica. As propostas poderão resultar de investigações individuais ou coletivas, apelando-se à participação de alunos de mestrado integrado/mestrado/doutoramento e investigadores/docentes, particularmente os que estão integrados no Mais do que Casas por via institucional.

Na primeira fase, com data prolongada até 12.05.2024, convida-se à submissão de um resumo de 500 palavras, definindo:

→ A linha temática #1, #2, #3, #4, #5, #6, #7

→ A pergunta de discussão Q1., Q2., Q3., etc.

→ A visão proposta: como, quem, quando, onde, o quê, quando.

A submissão será realizada após registo, a partir da plataforma conftool:

→ Template do resumo (word)

Após a revisão cega dos resumos, os autores das propostas aprovadas serão convidados a elaborar um artigo ampliado com 1500 palavras, a submeter até dia 10.09.2024.

→ Template do artigo (word)

Todos os artigos aprovados serão publicados nas atas da conferência.

→ Declaração de consentimento (word)

Após a realização do evento, serão selecionados 14 artigos, correspondentes a cada uma das perguntas de discussão. Os respetivos autores serão convidados a ampliar os seus artigos (3000/5000 palavras), tendo em vista a submissão em edição especial de revista científica.

REGRAS DE SUBMISSÃO e AVALIAÇÃO

Os autores poderão submeter apenas uma proposta.

Cada proposta terá um máximo de dois autores.

Todas as propostas serão sujeitas a processo de avaliação cega por parte da comissão científica do evento.

Os autores e respetiva instituição deverão ser apenas identificadas na plataforma conftool. No template fornecido deverá figurar apenas o ID de submissão atribuído pela plataforma.

As propostas aprovadas pressupõem apresentação obrigatória nas sessões paralelas do evento. A participação no evento é gratuita, mediante registo prévio.

→ Registo no evento: inscrição prévia (participação gratuita)

Os resumos aprovados serão publicados em Livro de Resumos do evento, com ISBN, a disponibilizar online.

Os artigos ampliados serão publicados em Livro de Atas do evento, com ISBN, a disponibilizar online.

Apenas as propostas discutidas no evento serão publicadas em Livro de Resumos e/ou Livro de Atas.

Cronograma

25-03-2024

25-03-2024Cronograma

12-05-2024

12-05-2024Cronograma

07-07-2024

07-07-2024Cronograma

10-09-2024

10-09-2024Cronograma

31-10-2024

31-10-2024Cronograma

22-11-2024

22-11-2024Cronograma

12-02-2025

12-02-2025Program

Síntese Programa

12 fev. 2025 FAUP

Program

Registo

Átrio de entrada da FAUP [Sala]

13h30-14h00 [Horário]

Sessões Paralelas

14h00-17h50 [Horário]

#1 – CIDADE E ESPAÇO PÚBLICO

Q1: Como criar modelos de cidade inclusiva através da habitação?

Átrio do Conselho Executivo [Sala]

Moderadora:

Teresa Calix

Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade do Porto (FAUP)

Comunicações:

→ A recuperação de uma memória em resposta à necessidade de habitação

Joana Sabino Barreto

Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade do Porto (FAUP). alumna

→ Comunidade inter-geracional

Joana Martins

→ Porosidade urbana e arquitectónica: o que é, porque importa, quando desapareceu e como recuperar?

Rita Castel’Branco

CiTUA, Instituto Superior Técnico, Universidade de Lisboa

→ Revisitar o Bairro da Malagueira: lições para o presente e o futuro das cidades

Rodrigo Coelho

CEAU-FAUP

→ Rumo à ressignificação da condição periférica da urbanidade

Andreia Garcia

Universidade da Beira Interior – Centro de Investigação em Arquitectura, Urbanismo e Design (CIAUD-UBI)

Q2: Que soluções habitacionais para a gestão dos vazios urbanos?

Salão Nobre [Sala]

Moderador:

Paolo Marcolin

Escola Superior Artística do Porto (ESAP)

Q2. (parte 1)

Comunicações:

→ Águas Cruzadas

Teresa Amaro Alfaiate

Arquitectura Paisagista, Instituto Superior de Agronomia, Universidade de Lisboa

→ Chão nosso: Nave para 2074

Álvaro Domingues

CEAU/FAUP

Helena Barbosa Amaro

CEAU/FAUP

Q2. (parte 2)

Comunicações:

→ Fazer Cidade ou Como habitar o Vazio Urbano?

Rodrigo Lino Gaspar

CEACT/UAL, CEAA/ESAP

→ Habitar a Linha. O Espaço Infraestrutural enquanto Habitar Contemporâneo

Tomás Abelha

Faculdade de Arquitetura da Universidade de Lisboa. alumnus

→ O vazio urbano como equipamento cultural alternativo na cidade do futuro: o caso do Zénite em Lisboa

Henrique Soeiro Andrade

Iscte – Instituto Universitário de Lisboa

Lorenzo Stefano Iannizzotto

Iscte – Instituto Universitário de Lisboa

#2 – MODELOS DE HABITAÇÃO

Q3: Como desbloquear inovação nas tipologias de habitação?

+

Q4. Como renovar modelos de habitação em contextos regulamentares restritivos?

Sala Plana [Sala]

Q3.

Moderadora:

Daniela Arnaut

Instituto Superior Técnico da Universidade de Lisboa (IST)

Comunicações:

→ Back to basics: repensar o tipo e os elementos da arquitetura

Tiago Lopes Dias

CEAU-FAUP

→ Casa Comum. A Habitação Intergeracional enquanto modelo de boas práticas

Inês Salema Guilherme

FAUP, alumna

→ Flexibilidade e Memória

Miguel Malheiro

CITAD, Universidade Lusíada Porto

Alexandra Saraiva

DINAMIA’CET, Universidade Lusíada Porto

→ Projeto Branda Científica: da reativação de um sistema de habitação estacional

Ana Luísa Salgado

FAUP/Biopolis

Nuno Valentim

FAUP/CEAU/Biopolis

→ The Freedom of Constraints: Insights from the Innovative Housing Projects of Caccia Dominioni

Mahdi Alizadeh

FAUP, CEAU

Luís Viegas

FAUP, CEAU

Q4.

Moderadora:

Helena Botelho

Faculdade de Arquitectura e Artes da Universidade Lusíada de Lisboa (FAAULL)

Comunicações:

→ Habitar o terroir Pico: a problemática de renovação dos modelos de habitação em paisagens culturais

Ana Laura Vasconcelos

Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade do Porto

→ a 123 da Rua da Bainharia

Olga Rita Álvarez Guillén

Faculdade de Arquitectura. Universidade do Porto

Teresa Fonseca

CEAU/FAUP. Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade do Porto

→ Residential Home Structures Plus 65 Years Old in Lisbon, Portugal. Automation of the Shape Grammar Rules

Filipe Montenegro Guterres

Universidade Lusófona de Lisboa

#3 – POLÍTICAS DE HABITAÇÃO

Q5: Que alternativas às atuais políticas de resposta à crise da habitação em Portugal?

+

Q6: O que se retira do programa SAAL na reposição do direito à cidade e à habitação?

Auditório da Biblioteca [Sala]

Q5.

Moderador:

Gonçalo Antunes

Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas. Universidade Nova de Lisboa (NOVA FCSH)

Comunicações:

→ O futuro do passado: o potencial da assessoria técnica, das rendas resolúveis e das cooperativas no acesso a habitação condigna

Ana Silva Fernandes

Centro de Estudos de Arquitectura e Urbanismo. Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade do Porto (CEAU-FAUP)

→ Porquê repetir os mesmos erros? Um olhar sobre o programa Construir Portugal e seu potencial impacto no ordenamento do território

Nuno Travasso

DARQ, Universidade de Coimbra; CEAU-FAUP

→ “Caminho para o Lar”. A Política e a Propaganda da “Casa Própria” como Herança a Questionar

Sérgio Dias Silva

CEAU

Q6.

Moderadores:

José António Bandeirinha

Departamento de Arquitectura da Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia da Universidade de Coimbra (DARQ)

Carlos Machado

Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade do Porto (FAUP)

Comunicações:

→ 50 anos depois: A evolução dos bairros SAAL em Lisboa e no Porto

Ana Catarina Costa

CEAU-FAUP (UPorto) e CEG-IGOT (ULisboa)

Ricardo Santos

CEAU-FAUP (UPorto)

→ A Herança Metodológica do SAAL: O Caso da Ilha da Bela Vista

Francisca Machado

Escola de Arquitetura, Artes e Design da Universidade do Minho

Eduardo Fernandes

Escola de Arquitetura, Artes e Design da Universidade do Minho

→ Prefabricação: uma solução fácil para um problema complexo

Diego Beja Inglez de Souza

Centro de Estudos de Arquitectura e Urbanismo. Universidade do Porto

#4 – REABILITAÇÃO

Q7. Como equilibrar as metas Net-Zero com a preservação do património habitacional?

+

Q8. Que abordagens inovadoras da reabilitação urbana promovem a habitação sustentável?

Sala do Janelão [Sala]

Moderadores:

Sofia Salema

Escola das Artes da Universidade de Évora (EARTES)

Maria Tavares

Faculdade de Arquitectura e Artes da Universidade Lusíada Norte | Vila Nova de Famalicão (FAAULN – Famalicão)

Q7.

Comunicações:

→ Contributos para um atlas de reuso do património construído

Teresa Cunha Ferreira

Centro de Estudos de Arquitectura e Urbanismo

Pedro Murilo de Freitas

Centro de Estudos de Arquitectura e Urbanismo

→ Programa Habitacional da Comissão para o Alojamento de Refugiados (CAR) – Da necessidade de Linhas Orientadoras para uma Intervenção

Pedro Sá

Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade do Porto (FAUP)

Q8.

Comunicações:

→ Cidades saudáveis e qualidade visual urbana – análise prévia à reabilitação urbana

Catarina Freitas

Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade do Porto

→ A Envolvente Habitável: Uma mudança de paradigma na reabilitação de edifícios

Cláudio Meireis

Escola de Arquitetura, Arte e Design da Universidade do Minho (EAAD)

→ O Reuso na Arquitetura: Uma Oportunidade para as Crises do Século XXI

Ana Filipa Batista Alvanéo

Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade do Porto

→ Slow Living e Perceção

Beatriz Neves

Universidade Lusíada Norte_Porto

Carla Andreia de Carvalho

Universidade Lusíada Norte_Porto

→ Converter edifícios devolutos em habitação acessível: referências para uma resposta habitacional adequada em áreas urbanas consolidadas

Joana Mourão

Centro para a Inovação em Território, Urbanismo e Arquitetura (CiTUA). Instituto Superior Técnico

#5 – ENCOMENDA PÚBLICA

Q9: Qual o balanço crítico aos concursos de conceção promovidos recentemente pelo IHRU e pela SRU Lisboa?

+

Q10: Em que medida os programas dos concursos públicos condicionam a proposta de modelos de habitação renovados?

Galeria Exposições [Sala]

Moderadores:

Ricardo Vieira de Melo

Faculdade de Arquitectura e Artes da Universidade Lusíada Norte | Porto (FAAULN – Porto)

Tiago Mota Saraiva

Faculdade de Arquitectura Universidade de Lisboa (FA-UL)

Q9.

Comunicações:

→ A encomenda pública de habitação a custos controlados em Portugal. Uma análise tipológica e construtiva

Rui Ferreira

Escola de Arquitetura, Arte e Design da Universidade do Minho

Carlos Maia

Escola de Arquitetura, Arte e Design da Universidade do Minho

→ Concursos de concepção – o desaparecimento da Arquitectura no debate sobre a Habitação

Nuno Castro Caldas

Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade do Porto

→ Habitação Crítica: Recolha e Paralelo dos Concursos do IHRU

Luís Santiago Baptista

Universidade Lusófona – Pólo Universitário de Lisboa

Nuno Griff

Universidade Lusófona – Pólo Universitário de Lisboa

Q10.

→ Habitação Crítica: o workshop como modelo de investigação tipológica

Filipe Quaresma

Universidade Lusófona de Lisboa

Maria Pais

Universidade Lusófona de Lisboa

#6 – HABITANTE

Q11: Como incluir os habitantes nas decisões que desenham o ambiente construído residencial?

+

Q12: Como facilitar o acesso dos habitantes às atuais medidas de apoio à habitação?

Auditório Fernando Távora [Sala]

Moderadores:

Roberto Falanga

Instituto de Ciências Sociais da Universidade de Lisboa (ICS-UL)

Gabriela Vaz Pinheiro

Faculdade de Belas Artes da Universidade do Porto (FBAUP)

Q11. (parte 1)

Comunicações:

→ A paisagem sonora no desenho participativo do espaço doméstico

Marina Santos

Universidade de Lisboa, Faculdade de Arquitetura

Jorge Nunes

CIAUD, Centro de Investigação em Arquitetura, Urbanismo e Design, Faculdade de Arquitetura, Universidade de alvanLisboa

→ Arquitetura e Ideologia: uma figuração do Comum, a partir de Casa Branca

Daniel Jesus

CIAUD – Centro de Investigação em Arquitectura, Urbanismo e Design, Lisbon School of Architecture, Universidade de Lisboa

→ How to Understand the Client using Applied Semiotics? Proposal of Communication Model and its application using the example of Bairro do Pego Longo, by Bartolomeu Costa Cabral

Krzysztof Michal Muszynski

University of Silesia, Katowice, Poland

Mariana de Oliveira Couto Muszynski

Departamento de Engenharia Civil e Arquitectura da Universidade da Beira Interior

Q11. (parte 2)

Comunicações:

→ Caminhar – Representar – Imaginar no Bairro da Emboladoura, em Guimarães, com crianças

Gabriela Trevisan

ProChild CoLAB

Mariana Carvalho

CEAU-FAUP

→ O papel da cultura em estratégias urbanas inclusivas. Perspetivas e práticas na Zona Oriental de Lisboa

Laura Pomesano

ISTAR-IUL

→ Ruas que contam histórias: arquiteturas de participação dos moradores da lomba

Francisca Weiner

FPCEUP

Joana Cruz

CIIE/FPCEUP

Q12.

→ Arquitectos de Família: Estratégias de Intermediação

Ana Pires

Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade do Porto

#7 – ADAPTAÇÃO ÀS ALTERAÇÕES CLIMÁTICAS

Q13: Como criar soluções responsivas e socialmente participadas de adaptação do espaço público às alterações climáticas?

EB 4.5_1 [Sala]

Moderadores:

Joana Mourão

Instituto Superior Técnico da Universidade de Lisboa (IST)

Teresa Marat-Mendes

Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE-UL)

José Carlos Mota

Departamento de Ciências Sociais, Políticas e Territoriais. Universidade de Aveiro (UA)

Q13. (parte 1)

Comunicações:

→ Assessment of Outdoor Thermal Comfort for an Age-Friendly and Climate Adapted Public Space

Rachita Klinmalee

Faculty of Engineering of the University of Porto

Helena Corvacho

CONSTRUCT (LFC), Faculty of Engineering of the University of Porto

→ Climate Change and Environmental Racism: Local Knowledge and Participatory Approach as a Tool for Adapting Public Space

Kiki Moreira Soares

Faculdade de Engenharia da Universidade do Porto

Fabiano Maciel Soares

Faculdade de Engenharia da Universidade do Porto

→ Desenho do espaço público responsivo ao stress climático: comunidade, envelhecimento, vulnerabilidade

Ana Martins

Centro de Estudos de Arquitectura e Urbanismo. Faculdade de Arquitectura. Universidade do Porto

→ Uma análise da circularidade do sistema alimentar a partir de práticas nos espaços públicos da cidade do Porto

Jeff Anderson

Faculdade de Engenharia da Universidade do Porto (FEUP)

Q13. (parte 2)

Comunicações:

→ Proposta de planeamento de uma rede de abrigos climáticos – aplicação à cidade do Porto

Maria Luísa Scharlau da Silva

FEUP

Sara Maria dos Santos Rodrigues da Cruz

FEUP

→ Um Lugar à Sombra. Uma análise comparativa das estratégias de mitigação das ondas de calor

Isabel Martinho da Silva

Departamento de Geociências, Ambiente e Ordenamento do Território, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade do Porto. CIBIO; Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, InBIO Laboratório Associado

Rita Moura

Departamento de Geociências, Ambiente e Ordenamento do Território, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade do Porto

→ A step-by-step framework for enhancing walkability and urban green resilience: guidelines for green and resting areas implementation using the WIEH Index

Franklin Gaspar

CITTA: Research Centre for Territory, Transport and Environment, Department of Civil Engineering, FEUP: Faculty of Engineering of University of Porto

Fernando Brandão Alves

CITTA: Research Centre for Territory, Transport and Environment, Department of Civil Engineering, FEUP: Faculty of Engineering of University of Porto

Q14: Como otimizar o uso de sistemas passivos e condições locais em modelos de habitação sustentável?

EB 4.5_2 [Sala]

Moderadores:

Fernando Brandão Alves

Faculdade de Engenharia da Universidade do Porto (FEUP)

Ana Velosa

Departamento de Engenharia Civil. Universidade de Aveiro (UA)

Comunicações:

→ A varanda mediterrânea como um arquétipo de bem-estar

Catarina Ribeiro

Faculdade de Engenharia da Universidade do Porto

Nuno Ramos

Faculdade de Engenharia da Universidade do Porto

→ Além do conforto: Redefinir a vivência térmica na arquitetura

Pedro Santiago

CEAU-FAUP

→ Arquitectura para mais do que humanos: Pensar a sustentabilidade a partir da revalorização de dimensões ecossistémicas qualitativas no projecto

Bruno Marambio Márquez

Centro de Estudos de Arquitectura e Urbanismo. FAUP

Sergio Elórtegui Francioli

Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso

→ Thermal and Natural Light Comfort Analysis of Bouça Social Housing Development in Porto, Portugal

Susana Alexandra Santos Pereira

University of Minho School of Architecture, Art and Design

Paulo Jorge Figueira Almeida Urbano de Mendonça

University of Minho School of Architecture, Art and Design

SESSÃO FINAL

Auditório Fernando Távora / Sala Plana [Sala]

18h00-19h15 [Horário]

Abertura

Comissão Organizadora STARBURSTING [FAUP]

Comissão Executiva Mais do que Casas [FAUP]

Mais do que Casas STARBURSTING [?]. “Quem”, “quando”, “o quê”, “onde”, “porquê”, “como” vamos habitar em 2074? 7 temas, 14 questões

→ Relator #1 – CIDADE E ESPAÇO PÚBLICO

Gonçalo Canto Moniz [CES – UC]

→ Relator #2 – MODELOS DE HABITAÇÃO

Rui J. G. Ramos [FAUP]

→ Relatora #3 – POLÍTICAS DE HABITAÇÃO

Simone Tulumello [ICS – UL]

→ Relatora #4 – REABILITAÇÃO

Teresa Cunha Ferreira [FAUP]

→ Relator #5 – ENCOMENDA PÚBLICA

Ricardo Agarez [ISCTE-UL]

→ Relatora #6 – HABITANTE

Joana Pestana Lages [ISCTE-UL]

→ Relatora #7 – ADAPTAÇÃO ÀS ALTERAÇÕES CLIMÁTICAS

Ana Rute Costa [Lancaster School of Architecture, Lancaster University, UK]

Encerramento

Teresa Novais, Luís Tavares Pereira [Curadores Mais do que Casas]

Comissão Organizadora STARBURSTING [FAUP]

Festa STARBURSTING

FAUP

19h15 – 21h30

Organization

PRESIDENTES

Gisela Lameira

Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade do Porto

Luciana Rocha

Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade do Porto

COMISSÃO ORGANIZADORA

Gisela Lameira

Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade do Porto

Luciana Rocha

Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade do Porto

Rui Jorge Garcia Ramos

Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade do Porto

Clara Pimenta do Vale

Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade do Porto

Filipa de Castro Guerreiro

Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade do Porto

COMISSÃO EXECUTIVA

João Pedro Xavier

Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade do Porto

Teresa Calix

Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade do Porto

Clara Pimenta do Vale

Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade do Porto

Filipa de Castro Guerreiro

Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade do Porto

José Pedro Sousa

Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade do Porto

Teresa Novais

Curadora Programa Mais do que Casas

Luís Tavares Pereira

Curador Programa Mais do que Casas

Scientific Committee

Ana Bordalo

Instituto Superior Manuel Teixeira Gomes (ISMAT)

Ana Cláudia Monteiro

Universidade Lusófona do Porto (ULP)

Ana Rute Costa

Lancaster School of Architecture, Lancaster University, UK

Ana Silva Fernandes

Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade do Porto (FAUP)

Ana Catarina Costa

Centro de Estudos Geográficos (CEG – ULisboa)

Ana Tostões

Instituto Superior Técnico da Universidade de Lisboa (IST-UL)

Ana Velosa

Departamento de Engenharia Civil. Universidade de Aveiro (UA)

Catarina Wall Gago

École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL)

Carlos Machado

Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade do Porto (FAUP)

Carlos Maia

Escola de Arquitetura, Arte e Design da Universidade do Minho (EAAD)

Daniela Arnaut

Instituto Superior Técnico da Universidade de Lisboa (IST-UL)

David Leite Viana

Departamento de Arquitectura e Multimédia Gallaecia da Universidade Portucalense (DAMG)

Fernando Brandão Alves

Faculdade de Engenharia da Universidade do Porto (FEUP)

Francisco Ferreira

Escola de Arquitetura, Arte e Design da Universidade do Minho (EAAD)

Gabriela Vaz-Pinheiro

Faculdade de Belas Artes da Universidade do Porto (FBAUP)

Gonçalo Antunes

Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas. Universidade Nova de Lisboa (NOVA FCSH)

Gonçalo Canto Moniz

Departamento de Arquitectura da Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia da Universidade de Coimbra (DARQ)

Guya Accornero

Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE-UL)

Helena Botelho

Faculdade de Arquitectura e Artes da Universidade Lusíada de Lisboa (FAAULL)

Hugo Machado Silva

Universidade Fernando Pessoa (UFP)

Isabel Martinho da Silva

Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade do Porto (FCUP)

Joana Mourão

Instituto Superior Técnico da Universidade de Lisboa (IST-UL)

Joana Pestana Lages

Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE-UL)

José António Bandeirinha

Departamento de Arquitectura da Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia da Universidade de Coimbra (DARQ)

José Carlos Mota

Departamento de Ciências Sociais, Políticas e Territoriais. Universidade de Aveiro (UA)

Luís Santiago Baptista

Departamento de Arquitectura e Urbanismo da Universidade Lusófona de Lisboa (ULL)

Maria Tavares

Faculdade de Arquitectura e Artes da Universidade Lusíada Norte | Vila Nova de Famalicão (FAAULN – Famalicão)

Miguel Reimão Costa

Universidade do Algarve (UALG)

Nelson Mota

Delft University of Technology (TU-DELFT)

Paolo Marcolin

Escola Superior Artística do Porto (ESAP)

Patrícia Santos Pedrosa

Universidade da Beira Interior (UBI)

Ricardo Agarez

Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE-UL)

Ricardo Vieira de Melo

Faculdade de Arquitectura e Artes da Universidade Lusíada Norte | Porto (FAAULN – Porto)

Roberto Falanga

Instituto de Ciências Sociais da Universidade de Lisboa (ICS-UL)

Simone Tulumello

Instituto de Ciências Sociais da Universidade de Lisboa (ICS-UL)

Sofia Salema

Escola das Artes da Universidade de Évora (EARTES)

Teresa Alfaiate

Instituto Superior de Agronomia – Universidade de Lisboa (ISA)

Teresa Marat-Mendes

Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE-UL)

Tiago Mota Saraiva

Faculdade de Arquitectura Universidade de Lisboa (FA-UL)